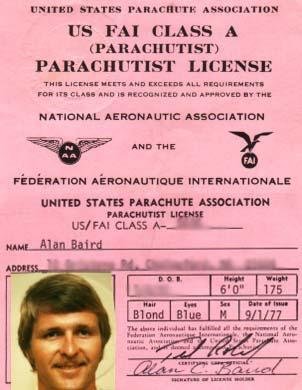

The Thirty-One Dollar Man.

The wind whipped my face, as I stood there in the drop zone. It wasn't the safest day for a skydiver with a round parachute, like mine. But I decided to jump anyway. Why? Because I'm stupid.

After a twenty-minute ride up to altitude, I climbed outside the airplane, and dangled off the wing strut. It was even windier out there. The plane's 60-mile-per-hour forward speed buffeted my body, but I hung on until my partner was sitting in the doorway. When he nodded and jumped, I let go and arched my back. The spread-eagle position kept me vertical for a few seconds, as my body burned off the forward speed of the airplane. Slowly, I started falling belly-to-earth.

We did a little relative work, or rather, HE did some relative work. I just kept my body in a hard arch, while he flew down to grab my wrists. But he had too much speed, and we began oscillating like a see-saw. First my feet went up towards the sky, then his. We both tried to correct the wild movements, by extending our feet at the appropriate moments. But nothing worked. We were both too new at this. So I pushed him off, and turned around to fly away. After a few seconds, I gave a warning wave and pulled the ripcord.

As my round chute inflated, I saw his ram-air chute unfold, a hundred yards away. He flew a few circles around me, laughing like a maniac: "Why don't you get a decent chute?" I flipped him the bird. He knew I couldn't afford it.

My Army-surplus round parachute had a cutout in the back, for stability and steering. In a normal descent, that cutout gave the canopy a forward speed of about 8 miles per hour. His expensive ram-air canopy, which looked like cross section from a swimming-pool air bed, could generate forward speeds from 0 up to 30 mph.

So I lined up my chute to face into the 25 mph wind. Subtracting the canopy's 8 mph forward speed, I was now scooting along at 17 mph. Backwards.

Plus, my standard rate of vertical descent was already 13 mph, given the design of my particular chute and my normal body weight. I suddenly regretted eating that sixth slice of pizza the previous night.

As I got closer to the ground, I realized that I was headed straight for a barbed-wire fence. So I turned the canopy around. Now I was whizzing along at wind speed PLUS canopy speed, instead of wind speed MINUS canopy speed. 33 mph, instead of 17 mph. And that was just the horizontal component. I was also dropping out of the sky vertically at my standard 13 mph. I thought, "This can't end well."

My brain kicked into overdrive, trying to compute the combined vertical/horizontal velocity. But as the ground rush intensified, the math got harder and harder to do. After the barbed-wire fence zoomed past underneath me, I instinctively turned the canopy around, to head into the wind again. The canopy dug in, and my body swung wide underneath it, much like a pendulum. The resulting forward swing of the pendulum canceled out the backward push of the wind, and I landed with very little horizontal speed at all. Easy squeezy.

My partner applauded, from 200 feet above: "Nice hook!" His chute was effortlessly holding steady against the wind, and he was coming down almost vertically. It was quite the contrast to my white-knuckle landing.

After repacking the chute, I decided to go again. Stupidity squared. This time, I chose to swan dive out the airplane door by myself. I had had enough of my partner's see-saw routine. So I practiced my free-fall spins: tilt both hands to the right, recover, tilt to the left, recover. Then somersaults: straighten my legs, tuck my hands and head, recover. Then rolls: reach to the side with one arm and one leg, recover. Easy squeezy.

Pop the ripcord, line up into the wind, no problem. But as I got closer to the ground, I noticed the wind speed had increased, during my ride up to altitude. The velocity situation was looking ugly. No fancy "hook" maneuvers were going to save me this time. At 100 feet above the ground, I went zipping past some horrified onlookers. I yelled "HELP!" Groundrushgroundrushohcrapohcrap. Darkness.

They tell me that I was about 20 feet above the ground when a sudden gust of wind blew my chute backwards. My body, of course, responded less dramatically to the wind gust, so a slightly different pendulum effect was created this time. Have you ever wanted to climb to the top of a double-decker bus careening through the streets of London at 40 or 50 mph, and jump off? Facing backwards?

Long story short: I was smashed into the ground by this pendulum. Then my unconscious body was dragged 200 feet by my still-inflated parachute. Luckily, a nice woman had sprinted to my aid, when I yelled "HELP!" Somehow, she caught the runaway chute and deflated it. She waited for me to regain consciousness, then asked, "What hurts?" She drove me to the local hospital and waited while my elbow was X-rayed. She commiserated with me, when the doctor said the anesthesiologists were on strike, and I couldn't get the operation I needed. She drove me back to my car, after the doctor packed my shattered left arm into a temporary plaster cast. Then she waited patiently while I tried to figure out if I could drive my stick-shift car 50 miles back home, across the San Francisco Bay. I vowed to return her kindness, somehow.

The trip turned into a blur of pain, so I stopped at a liquor store for a fifth of tequila. The bottle was nearly empty when I arrived home. It helped quiet the screaming elbow, but it only intensified the agony of the concussion.

Over the next few days, I found out that my elbow needed an immediate operation, or it would end up f*cked. I'm pretty sure that was the medical term they used: f*cked.

And since the anesthesiologists were on strike, the only place that could operate on me was the teaching hospital at the University of California, San Francisco. They had "baby" anesthesiologists: anesthesiologists in training. They also had "baby" surgeons. My baby surgeon told me that he had never done this operation before, but not to worry, because the surgery would be supervised by his teacher, a "real" surgeon. I wasn't mollified, but what could I do? If I didn't let him operate, my elbow would end up f*cked. Medically f*cked.

After the surgery, he told me an interesting story: when they handed him the 6-inch Leibniz screw that was supposed to knit my shattered elbow back together, it was twisted. So he sent it back to the supply room, and asked for another. When the second screw arrived, it was also twisted. That's when his supervising surgeon picked up the screw and bent it back and forth. It turns out that Leibniz screws are designed to have great strength in the long direction, while offering great flexibility in the side-to-side direction. Since the outside forearm bone, the ulna, is slightly curved, the screw needs to curve with it. When the baby surgeon finished telling this story, he laughed. He thought it was funny as hell. Me? Not so much.

So I went home to heal. After several weeks, the baby surgeon took off my plaster cast. I was shocked at how much my arm had shrunken. He said I would probably regain only 75% of the full range of motion. But Macho Stupido hopped on his motorcycle, and started riding. After a month, the arm looked and moved normally.

A few months later, I mustered some courage and drove back out to the drop zone. I found the nice woman who had been so kind to me on the day my arm was broken, and I offered to buy her a couple of jumps. She seemed genuinely touched, and invited me to come along with her and her boyfriend. They knew a lot more about relative work than my old partner. When they flew down to grab my wrists, there was no see-saw oscillation. And right there, at 6,000 feet and terminal velocity (120 mph), the nice woman kissed me. It was my first kiss in free fall.

Even to this day, if you place your palm on my left elbow, you will feel an icy-cold spot. And I still have the itemized hospital bill that lists $31.00 for a Leibniz screw.

book

bookPowered by Blogger